The three blobs middle-left are NHL2:sand 1:2.5 (no cement). By the end of the project, we had adjusted to 1:2 to make the sand color and texture match better, and reduce a crumbly sand sensation.

Middle-right is a lime:sand 1:2.5 mortar made with "ag lime" picked up from a local farm store. Don't use ag lime! It's crush up calcium carbonate which has already cured. You want calcium hydroxide that cures between your bricks into calcium carbonate.

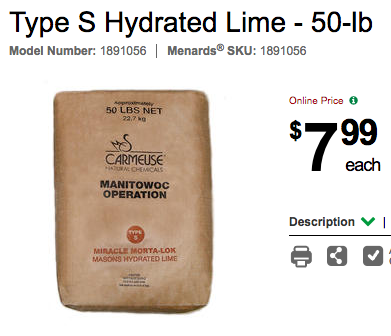

The right two blobs are a lime:sand 1:2.5 mortar using Type-S Hydrated Lime (not Type-S mortar) from the local Menard's store and sand aggregate that was a clean mix of several sizes of sand. It works, but it looks weak. This is what the ancients used with ratios of 1.5 up to the over-assumed 3.0.

The blob on the brick was doing adhesion tests, and the blobs on the bottom were used for strength tests (punction, cracking, chipping)

Many modern masons have high volume constructions skills that are not

suitable for restoration work. Putting Lowe's or Home Depot Type-N

mortar (unrelated to Type-N

Many modern masons have high volume constructions skills that are not

suitable for restoration work. Putting Lowe's or Home Depot Type-N

mortar (unrelated to Type-N  When

you're sure you have the right lime, check again. A prominant DIY help

website showed the picture duplicated here on the right side. The

picture represents what you'll find out there. Look at the red-arrow annotation. It

says "hydrated." Then see "for Agricultural Uses". Then look at the

first sentence of Wikipedia for Agricultural Lime: "Agricultural lime,

also called aglime, agricultural limestone, garden lime or liming, is a

soil additive made from pulverized limestone or chalk."

When

you're sure you have the right lime, check again. A prominant DIY help

website showed the picture duplicated here on the right side. The

picture represents what you'll find out there. Look at the red-arrow annotation. It

says "hydrated." Then see "for Agricultural Uses". Then look at the

first sentence of Wikipedia for Agricultural Lime: "Agricultural lime,

also called aglime, agricultural limestone, garden lime or liming, is a

soil additive made from pulverized limestone or chalk." Pulverized

limestone or chalk is NOT hydrated lime and is NOT the right lime to

use in masonry work. Pulverized limestone and chalk is not the same as

hydrated lime. The product pictured could be hydrated lime or could be

ag lime, but it cannot be both! I know this is confusing because a

mason I hired showed up with bags of ag lime and I insisted he not use

it. I ran some test and showed him that Hydrated Lime makes a decent

but weaker than Cement mortar. The ag lime test piece makes nothing - it crumbled when

squeezed in our hands. If you build a house out of ag lime, the wall

will wash away with the rain and your wall will fall down!

Pulverized

limestone or chalk is NOT hydrated lime and is NOT the right lime to

use in masonry work. Pulverized limestone and chalk is not the same as

hydrated lime. The product pictured could be hydrated lime or could be

ag lime, but it cannot be both! I know this is confusing because a

mason I hired showed up with bags of ag lime and I insisted he not use

it. I ran some test and showed him that Hydrated Lime makes a decent

but weaker than Cement mortar. The ag lime test piece makes nothing - it crumbled when

squeezed in our hands. If you build a house out of ag lime, the wall

will wash away with the rain and your wall will fall down! These are ~not~ sealants, like "Thompson's water seal". For a

healthy brick wall, film forming sealants are bad. Penetrating

repellants

are good.

It's of like Gortex for bricks - keep water out while water vapor

passes through. The bricks have to breath, not receive a

waterproof coat or else water vapor will be trapped IN the brick due to

temperature gradient condensation. You'll know if you're buying

the correct stuff because good repellants are expensive

– maybe $200 for 5 gallons of 7% siloxane, with a coverage of 90-150

ft2 per

gallon. A 40% silane mix may be twice that cost. Kryton Hydropel

sells through Home Depot with a coverage of about 100 sqft/gal for soft

bricks and costs $97 per gallon. Ouch.

These are ~not~ sealants, like "Thompson's water seal". For a

healthy brick wall, film forming sealants are bad. Penetrating

repellants

are good.

It's of like Gortex for bricks - keep water out while water vapor

passes through. The bricks have to breath, not receive a

waterproof coat or else water vapor will be trapped IN the brick due to

temperature gradient condensation. You'll know if you're buying

the correct stuff because good repellants are expensive

– maybe $200 for 5 gallons of 7% siloxane, with a coverage of 90-150

ft2 per

gallon. A 40% silane mix may be twice that cost. Kryton Hydropel

sells through Home Depot with a coverage of about 100 sqft/gal for soft

bricks and costs $97 per gallon. Ouch.